Stakhanovite Philosophers’ Workbench: Atkins and Lassiter

Relentless Adjuncting, Existential Graphs, and Non-Rejection

Try to envision a philosopher writing a paper while climbing a mountain. Or imagine that mountain-climbing philosopher writing while wearing a backpack loaded with rocks. In its distinctively twisted way, writing philosophy is hard, but most of the time, academic philosophers fuss with words in relative ease—in their offices or homes, maybe during summer holidays or while on a sabbatical from teaching. But I’ve known a few philosophers who have steadily set down words while dealing with setbacks and challenges of a variety unknown to most members of the professional guild. Two of those philosophers are Richard Atkins and Charlie Lassiter.

I met Atkins and Lassiter around 2012. They had done time in a Ph.D. program where I then worked but have since left. It is allegedly the business of a philosophy Ph.D. program to train new professional philosophers, and it is the job of a program’s Placement Officer to support graduates during their search for employment after graduation. For a few years, I was my department’s Placement Officer and had the opportunity to work together with Atkins and Lassiter. They were both hired into tenure-track jobs teaching philosophy and, years later, both of them earned tenure—Atkins at Boston College and Lassiter at Gonzaga University.

Perhaps the mountain-climbing analogy suggests the two philosophers’ backbreaking paths from graduate school to the academic tenure track, but a different analogy resonates even more. These two didn’t go up the mountain—they worked beneath it.

They are a little like Alexi Stakhanov (1906–77), a jackhammer operator who toiled in Russian coal mines in the 1930s. Stakhanov gained worldwide celebrity for feats of mining productivity that far outstripped what was believed possible. One day in August 1935, he mined 102 tonnes of coal in under six hours—14 times his quota—and then in September surpassed his own record by mining 227 tonnes in one shift. The name “Stakhanovite” was given to workers across Soviet industries, from manufacturing to farming, who shattered production records. In celebrating the Stakhanovites, Joseph Stalin once remarked that they “have learned to count not only the minutes, but also the seconds.”

Teachers of philosophy do not mine coal, but we can still measure their labours. In 2004, when Atkins and Lassiter enrolled in a Ph.D. program, they received no funding from their department or university. No funding for the Ph.D. was (and is) relatively uncommon in their academic field. And let me add that they were not able to enroll in classes for free—neither received tuition remission. They paid their own way through grad school while living in one of America’s most expensive metropolitan areas, New York City. To support themselves, they picked up part-time jobs. At one point, Lassiter handed out fliers on Friday and Saturday nights for a bar in Hoboken, New Jersey; Atkins worked as a secretary at a church and then as a production liaison at a publishing company. But, mainly, the two grad students became adjunct instructors—while simultaneously completing their Ph.D. program requirements by writing term papers, passing comprehensive exams, and writing dissertations.

I compiled some figures about their teaching. Lassiter taught nearly 50 courses before he began a tenure-track job in 2013. He ordinarily took on three courses in Fall and Spring semesters, plus three or four courses during the summer. His courses were in areas including Ethics, Intro to Psychology, Intro to Sociology, College Writing, and Ancient Greek Philosophy at institutions such as Rutgers University–Newark, Georgian Court University, and Monroe College. Similarly, before starting a tenure-track job in 2014, Atkins taught over 60 courses. As a graduate student, he would usually cover between two and five courses every year, but after he graduated with a Ph.D. in 2010, his course load increased to four or five courses each semester; he lectured on Ethics, Intro to Philosophy, and History of Philosophy at Iona College and New York University. By my rough estimate, Atkins and Lassiter each taught around two thousand students during their pre-tenure-track years. They accomplished all of this while steadily learning, writing, and publishing. They are Stakhanovite philosophers.

Years after meeting them, I wanted to know: What compelled them to write and how did they work during those precarious years before finding tenure-track employment?

Other conversations on The Workbench have been conducted largely over email and with occasional exchanges by telephone. For this one, I met with my interview subjects on Zoom. The three of us talked on two occasions in October and December 2022. We recorded and then transcribed the Zoom conversations. In September and October 2024, we edited the transcriptions and added some new material from discussions over email.

NB: What’s the worst writing advice you’ve ever been given?

CL: “Find your voice.” I’ve actually tried that!

NB: Where did you look?

CL: At first, I set aside time to “find my voice” that was separate from writing time. I would write something and ask, “Is this my voice? Is this how I want to sound?” Whenever I put words on the page, I was overthinking and wondered if I sounded sufficiently erudite. There is no finding your voice. More sensible advice in the neighborhood is: recognize your voice. Just write and rewrite until you like to read what you’ve written. For example, in one paper, I needed to give a brief overview of the state of play. Everything I tried felt stilted and awkward. In exasperation, I typed, “Once upon a time, there was a philosopher who…” and that felt right. That’s a case of recognizing, but not finding, your voice.

RA: One piece of bad advice is that if ideas are not coming to you easily, they’re not worth pursuing or that you should work on something else. A second bit of bad advice is to write as though you’re explaining your ideas to a child.

NB: Here’s a line from the English literary critic Cyril Connolly: “The only way to write is to consider the reader to be the author’s equal; to treat him otherwise is to set a value on illiteracy.” OK—we started with a question about lousy writing advice, but I feel like I’m getting ahead of myself already. How did you go into philosophy, of all things?

RA: When I was in high school, my family moved from Ohio to Iowa, and I didn’t have any friends. And I was sitting in my bedroom in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, reading Stephen King and Michael Crichton novels and thought, “I need to read something else.” I went to the bookstore and wandered through the aisles looking for something different. Nothing caught my attention in the poetry or history sections, but I ended up in the philosophy section and spotted a copy of Plato’s Republic.

NB: What’s wrong with Jurassic Park?

RA: Nothing, but I’d already read the book and seen the movie. Well, I don’t know what possessed me to buy Republic. But I had taken all the math and English classes offered at my high school. And in Iowa high schools, they cover the cost of any college classes you take, if you complete all of the courses the high school offers. Coe College was just across town. So I said, “Well, I could take math at Coe College, but I don’t want to take any more science. I want to take a course in philosophy instead.” And I loved it. My professor, who is still at Coe, was named John Lemos.

NB: Yes, and John Lemos has a brother who’s a philosopher: Noah Lemos at William & Mary. And their dad, Ramon Lemos, was a philosopher. So, where did you go to college, Richard?

RA: Wheaton College—the one in Illinois. I majored in philosophy. I went there because my dad said he wouldn’t pay my college tuition unless I did. I had wanted to stay at Coe. And that reminds me of something else in my background. I grew up in a relatively conservative Christian home. My mother and my grandmother had diametrically opposed theological positions. Late into the night, they would debate predestination and God’s foreknowledge and stuff like that—all pretty philosophical. Part of what introduced me to philosophy is my religious upbringing.

NB: How about you, Charlie?

CL: I read some existentialism in high school as an angsty teenager, but I wasn’t really introduced to philosophy until college. I started out as a psychology major at a small Catholic school in New Jersey, St. Peter’s College. I remember taking a class on abnormal psychology, and it made absolutely no sense to me. I was a bit disillusioned with the subject, but around that same time I took a course in American philosophy. It was eye-opening for me.

Let me try to give you a sense of my surprise. I grew up in an abusive household. In the course, we’re reading William James about free will and the will to believe. And James proposes the idea of meliorism—it’s a theme running through a lot of his work. You can bet on things getting better, right? That’s what the optimist says—no matter what, it will turn out okay. But the meliorist says, “Alright, it can turn out okay. If you try to do something about it, things can get better.” Things can get better if you work at them. I came to the class having suffered from depression and borderline personality disorder for most of my life. Reading James from that dark place, a light bulb went on. It was like, “Holy shit, things can get better—you could actually do something about your life.”

NB: I know you know William James’ own personal story. There’s depression, mental illness, family crises.

CL: I didn’t know James’ story until after my revelation. Learning about it brought me some solace. But there was no going back: philosophy seemed to be where my destiny lay.

NB: I’m interested in the transition from college to graduate school. What did that look like for you, Richard?

RA: Well, when I finished college, I wasn’t sure I wanted to go to graduate school. Honestly, at that time, I desired more to be a poet than a philosopher.

NB: What sort of poetry were you reading?

RA: I read a lot of American poetry. I liked the Beats, but also French poets—Verlaine and Rimbaud. I had a huge collection of poetry, which I eventually sold, and regret giving it up. Back then, I was dating someone who was living in Minneapolis, and I graduated from college, moved there, and moved in with her. I got a job working in a wholesale book distributor—basically, a middleman between publishers and bookstores. And I was on my feet 8 or 10 hours a day, earning minimum wage. And I thought, “This can’t be what I do with my life.” So, I decided to get a Master’s degree in theology.

NB: Another reliable path to the minimum wage?

RA: Yeah, but if you’re a pastor, you can at least get a housing subsidy. So I hopped in my car, I drove cross-country, visited different schools, and ultimately enrolled at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, California. For two years, I studied philosophical and systematic theology. Unlike Charlie, I had never taken a class in American philosophy, but while I was in Berkeley I ended up studying the work of Charles Sanders Peirce and other American philosophers, under a Jesuit theologian named Donald Gelpi. And I pretty much knew then that I wanted to work on American philosophy. All these years later, I mainly work on pragmatism and Peirce.

NB: You had been reading and writing poetry before your exposure to Peirce. Was there something about Peirce’s writing that struck you?

RA: I wouldn’t say so. What attracted me was the systematicity of Peirce’s thinking. I have always enjoyed conceptual systems. And I don’t think my interest in poetry has influenced my philosophical work, at least not in any discernible way. But reading poetry did teach me to be a more careful reader.

NB: What happened to your old poems?

RA: I never published any of my poetry. It’s all sitting in a box in my basement. Sometimes I think of rereading them. Then I think they’re probably terrible and I’ve got other things to do anyway.

NB: Charlie, tell me about your transition from college to graduate school.

CL: I went with the advice I was given, which was: Don’t take time off between college and graduate school. I dove right in.

NB: What type of dive did you make?

CL: I was hoping for something graceful, like an osprey, but it was more like a penguin doing a bellyflop.

NB: Oh no. Tell me more.

CL: It was totally intimidating. There’s a funny story involving Richard. In the first semester, there was a meet-and-greet for new graduate students in the library foyer. Everyone was standing around chatting and Richard mentioned Leonard Cohen. And I asked, “Who’s Leonard Cohen?” I might as well have said that I shot the Pope—you could almost hear the record scratch as people looked at me, “You don’t know who Leonard Cohen is?” After that I got defensive and I was like, “Screw you—I bet Leonard Cohen sucks.” I felt intimidated because there seemed to be some sophisticated, shared cultural knowledge that I hadn’t tapped into. Well, I spent my first few years in graduate school feeling like I didn’t belong.

NB: Lots of philosophers are afflicted by imposter syndrome. I remember the first time I realized there are highly successful, senior philosophers who suffer from it. Also, I’m Canadian and, trust me, it’s fine to know nothing about Leonard Cohen—if you ask me, he’s overrated.

CL: If a Canadian says it’s OK, then it must be. This might sound a little bizarre but I was convinced during college that I got good grades because people felt sorry for me. Being in grad school without any kind of funding made that all the worse. Everybody else was clearly much smarter than me. My first roommate won a fancy fellowship where he got paid and didn’t have to do a stitch of work. He was a great guy, but being around him sometimes exacerbated the feeling of not belonging. I felt it was only a matter of time until I got called into the department chair’s office and given the boot.

NB: I still can’t believe you two went to grad school without any funding—and survived.1

RA: I’m just going to add a little comment here. Charlie, remember our first year? We formed a reading group, just the two of us. It was on Charles Peirce’s existential graphs.

NB: That was 2004? You two were the only Ph.D. students in America studying Peirce’s existential graphs.2

RA: Charlie might’ve been feeling like a fish out of water, but he understood that material way better than I did. I depended on him to understand it.

CL: You’re kind—I felt the same about you!

RA: From my point of view, Charlie was definitely the student who grasped the logical side of things better than most of our peers.

NB: How did you stay on track with your writing while teaching so many courses? Many academics would have quit, Richard, when they were on year-to-year contracts. Teaching five or six courses per semester plus summer teaching, which you did when you graduated, is daunting, especially given you also continued to write and even produced a book manuscript. Those circumstances breed impatience and disappointment. Somehow, you kept your head down. I’d like to know: How?

RA: Yeah, I would say I didn’t feel like quitting. But keeping my head down required a lot of self-discipline.

NB: How did you organize your life? Where did you do your work?

RA: I worked wherever I could. In our apartment in Queens, I had a desk in the living room. Other times, it was at the kitchen table. My wife has pictures of me sitting in our apartment, holding our daughter, while working on my dissertation. As far as organizing my life, I’ll tell you the same thing that I tell all of the philosophy grad students at BC. One of Charlie’s colleagues, Greta Turnbull LaFore, who went to grad school at BC, coined the name for it—the “Atkins Diet.” Every day, read at least one essay or chapter related to your research, write at least one paragraph, and jog at least one mile.

NB: How did you stick with that routine over the years? Was it habitual? Was someone encouraging you?

RA: I committed myself to doing it and I wouldn’t stop. Some days, laying down for bed, I’d ask: Did I do all my things today? If there was something I missed, I’d jump out of bed at midnight. I had to do it. Otherwise, I would have a guilty conscience.3

NB: Did you have a similar strategy, Charlie?

CL: My strategy wasn’t as regimented as Richard’s. One thing I did was keep some work materials on hand wherever I went. I still do that. I always have pen and paper and a book or journal article. And if I ever had any downtime, standing in line at a grocery store or at 2 in the morning when I’m trying to get my kid back to sleep, I would pull out something to read and try to saturate my time with as much reading and writing as I could.

NB: When you break work into little pieces, isn’t it hard to make progress? Many writers can’t do anything with thin slices of time. Or at least they believe they can’t.

CL: Whereas Richard’s superpower is following the Atkins Diet, I guess my strength is working with those little 15 minute blocks. I’ll hammer out as many words as I can or read as much as I can.

NB: I’m imagining a hamster or gerbil racing on a wheel—a blur of fur for 15 minutes. And then you go back to eating pellets or whatever. Is that how you wrote papers? You would take your 15 minutes, try to get something down on paper, and persist until you eventually had a draft?

CL: Exactly. When I was in grad school, my kids would nap for an hour-and-a-half or so. Most of that time I’d use for grading or lecture prep. And then if I had 15 minutes before they woke up, I’d sneak in a few words on my dissertation or read a few paragraphs of an article. I would leave a lot of breadcrumbs for myself. With my last thirty seconds of writing as my kid is waking up, I’d add quick clips and paraphrases into the document. ‘Here is where you left off’ or ‘This is where you’re headed.’ Leaving breadcrumbs helped me work in shorter blocks.

NB: That’s a helpful technique: Be brief under time pressure and fill in the blanks later. You carry work around with you, but did you ever lose a paper you were working on? There’s a story about John Dewey leaving a draft book manuscript in the backseat of a taxicab in New York City. The manuscript vanished—it would have been Dewey’s last book.4

CL: Fortunately, I have never lost a draft paper!

NB: Richard, you wanted to write a paragraph each day, but you must have been working on multiple projects at once, right?

RA: A minute ago, Charlie used the phrase “saturate your time.” That’s spot on for me. Sometimes you’re sitting in the waiting room for an appointment, and you spend that time reading an article. I still do that. Like Charlie said, with writing, you know where you’ve been and where you want to go. You might start the first sentence of a new paragraph before time runs out. But occasionally there’s a day when you don’t really have anything to do. On days like that, from the start of my day to its end, I would work on essays, nonstop, and sometimes I’d write an essay in a day.

NB: You’d sit down and write a full paper in one day? You mentioned the Atkins Diet—but, boy, that’s the Atkins Overdose.

RA: Yeah, that paper would have been simmering in my mind for a long time. I would sit down and do as much as I could do in a day.

NB: Then you’d return to the draft and refine it?

RA: Oh, yes, there’s no way for me to escape the editing process. My papers never emerge fully formed.

NB: Do you have any tricks for editing draft material?

RA: When editing draft material, I read it aloud to myself. I also read the first sentence of every paragraph to make sure that the main ideas are conveyed just in those sentences. I read the paper backwards, sentence by sentence or section by section—not backwards word for word. After I finish a piece, I will often set it aside for a month or two, at least, and then come back to it with fresh eyes. That helps me see where there may be gaps in the argumentation or where something isn’t clear.

NB: One of my favourite high school teachers was a poet and he once told his class: Write your poem and put it in a dresser drawer for seven years. Charlie, what are your editing tricks?

CL: Let me think about that. One thing I do is that if a sentence looks too long or has too many short words in a row, I’ll usually split it into two sentences or rephrase it to make it tighter. And, like Richard, I read the draft aloud. If I get lost reading something and I’m the author, the reader isn’t going to be better off! I also pay a lot of attention to the introductory paragraphs and try to find a “hook.” Usually I start with a story, anecdote, or surprising research. Readers’ bandwidths are likely maxed-out, so I try to write in a way that’s engaging. I keep Kurt Vonnegut’s advice in mind: Pity the reader.

NB: Vonnegut’s advice is almost as helpful as Mr. T’s advice to pity the foo’.

CL: As long as we don’t confuse the latter with the former!

NB: By the way, I’ve noticed that you come up with good opening hooks. Here are the opening lines from your article “Could a robot flirt?”:

I am awful in social situations. Flirting is completely lost on me, so I’m fortunate that my wife-to-be already understood this and made a conspicuous move on me when we were younger. Despite the dullness of my social acumen, I can (and do) take heart in this: no matter how bad I am at social cues, I’m still leaps and bounds ahead of what our best social machines can do. If I had to put money on it, I’d say I’ll always be years ahead.

Could a robot come up with good opening hooks?

CL: I asked ChatGPT to write a funny opening line for an essay on machine learning. It spat out, “In a world where even toasters are getting smarter, machine learning burst onto the scene like an overeager student who accidentally drank a gallon of coffee before the exam.” Not my cup of tea, but maybe it tickles some folks?

NB: Earlier, I asked you briefly about quitting, Richard, and had meant to come back to that. Did you two ever think you’d quit philosophy?

RA: Yes, I thought about quitting all the time. What stopped me is that I wasn’t sure what else I would do or was even qualified to do.

CL: I was in the same boat as Richard. I would look at the trucks rolling by on the New Jersey Turnpike and daydream, “I could be a trucker…” More realistically, I probably would have taught English in a high school. But I didn’t really have to talk myself out of quitting—I had neither the time nor the energy to seriously consider another profession. Maybe after a few years of adjuncting following the Ph.D., I’d have given up.

NB: So when did you two first try writing not for a course or professor, but instead for publication?

RA: Here’s a little story. In grad school, I was writing on Peirce, so naturally I wanted to publish in the Transactions of the Peirce Society. I remember writing an essay and thinking it was brilliant. It covered a lot of terrain at a really abstract level. I submitted it to the Transactions and it was rejected. I wrote to the editor, Peter Hare, expressing my disappointment, and he said, I’m not going to quibble with you about your paper: it’s simply unpublishable.

NB: Your brilliance was unpublishable! How did that feel?

RA: Well, I decided to submit another piece I had written on Peirce’s classification of the sciences. How to classify the sciences was a major area of inquiry in the late 19th and early 20th century, and Peirce first tried a classification modeled on biological taxa and then switched to classifying them by some categories derived from logic. The paper was just exploring the development in his thought. I had a very narrow point to make—a tiny contribution to a minor discussion in the literature. And that paper got accepted for publication. Then it dawned on me: If you want to publish, you should say very little.

NB: The maxim needs a name.

CL: How about “Atkins’ axiom of non-rejection”?

NB: That’s such an interesting realization to dawn on a young scholar. The contrast between the two situations is sharp. For the one project, you have an ambition to say something new, but the journal has no time for it. The other project is a small contribution at the edges of a minor debate. And that one’s a winner. So, you take away a lesson about how to succeed. Don’t be ambitious.

Of course, if you’re not aware of what’s happening, you could easily lose contact with your own standards, don’t you think? You let other people decide what you should do, to some extent. It’s the difference between trying to go by your own lights and deferring to the scholarly community’s lights. Is that how you looked at it? Did you just decide to defer?

RA: That was pretty much it. I thought, “Well, I need to publish and I’m not going to play games.”

NB: But did you have doubts about the intellectual merits of the more ambitious project? Did you assume that Professor Peter Hare simply knows more than you?

RA: My experience has been once you get a bit of a foothold in the field, things go more smoothly. You can make bolder claims with less support.

NB: What happened to the rejected paper?

RA: That first essay had to do with William James, Peirce, and phenomenology. Its central idea was bunk. But some of the ideas in that piece did end up in my book on Peirce’s phenomenology. My advice for beginning scholars, especially ones working in the history of philosophy, is to make very small contributions in non-contentious ways, because you need to get past the gatekeepers. If you can’t show your papers at the gates, you don’t get in.

NB: Do you want to comment on journal rejection, Charlie? When did you first submit a paper to a journal?

CL: I first started submitting papers when I was two or three years into graduate school. My motivation was similar to Richard’s: I knew I needed to publish to have any chance of making my way in the academic world. Like Richard, my first few papers were expansive, bold projects—along the lines of “Everybody is wrong about this topic, except me.” Those papers all got rejected, of course.

NB: What eventually changed?

CL: I am going to appeal to “Atkins’ axiom of non-rejection.” I started writing on niche topics, trying to make small contributions. Those papers were accepted by journals a lot more quickly. My first paper in a journal put out by a major publisher was about the causal-constitution fallacy debates concerning extended mind. Told you—super niche stuff! But I didn’t have Richard’s degree of self-awareness. He was able to formulate what he needed to do to publish. I bumbled along until I found a strategy that worked, at least sometimes. My own experience resonates with Richard’s, though. Don’t aim high, aim middle. Make small contributions to small problems. That’s how you get your start.

NB: Maybe that’s good advice. But as a social policy, it seems too conservative, too boring. You’ll get a field choked with minor contributions and no big, ambitious perspectives. But in philosophy shouldn’t we encourage newcomers to rethink the assumptions, methods, and even the questions? In a way, philosophy’s most compelling propagandists, like Descartes, said they were exploding everybody’s earlier ideas and rebuilding from scratch. You might think that a kind of radicalism is good to encourage. Of course, maybe we don’t need radicalism because the field already has reliable methods and now it is just a matter of incremental progress. But I doubt most areas of philosophy are like that.

RA: Well, I’ll jump in and say something about your reason against the advice. I don’t agree with it at all. No other academic field would rule out making minor contributions to a discussion or a debate. I mean, journals are filled with that. Why should that be a problem?

NB: Let’s try to get clear on what the policy is. I thought the policy was an action-guiding recommendation for early-career researchers: Make a minor contribution so you don’t get rejected. I agree that journals should be open to various kinds of contributions, but I also don’t want the field to discourage big new ideas. Following the axiom of non-rejection means avoiding certain big dreams and settling for small dreams instead.

RA: I guess I wouldn’t put it quite that way. My advice is when you’re starting, start small. You can have big dreams. But think of the dreams as in the distance that you’re gradually moving towards.

CL: I think I agree with Richard on this one. If your goal is to get published in academic journals, starting small is the best way to achieve that goal. That said, maybe you’re the disciple of a superstar and you can be shepherded into big conversations. In that case, the advice might be different, but that doesn’t apply for most people.

NB: The motivation for the axiom of non-rejection is that the gatekeepers are so difficult to pass by, and the best way to do that is by adopting the normal standards and questions and styles. But maybe you look around and begin wondering: Well, how did I get here? Do I really care about pleasing these people?

CL: The ideal situation would probably be where you have a big, ambitious project. And then you take it piecemeal and figure out how to get bits of your project into conversation with what’s already out there, right? And probably the easiest way to do that is to enter these secondary or tertiary debates. Then, basically, you get your ambitious project to begin to grow by planting little seeds.

NB: Good analogy. Maybe that’s similar to what Richard was saying a moment ago: there’s a more dynamic strategy where you think about both long-term and short-term goals. I think that becoming aware of the dominant conversation is important for knowing how to make your ambitious project more palatable to gatekeepers. If you decide you want them to be your audience, in part, you need to know how they think, how they talk, what motivates them to read a text.

RA: I also think there’s an important distinction between pursuing your intellectual goals and professional goals. Early career scholars have to realize that they’re just at the start of their intellectual careers. But in order to pursue their long-term intellectual careers, they need to succeed in the short-term professional career.

NB: Imagine coming of age as a junior academic at the end of the Soviet Union. In 1991, in the span of a few months, the USSR was wiped from the map. That sort of social change is hard for us to fathom—there’s an empire and then, poof, it’s gone. I want to be cautious, but I have a taste for desperate metaphors to try to illuminate what early 21st century English-speaking academic philosophy feels like for young, unestablished researchers. For some of them—me, not so long ago—it’s like waking up one morning and realizing that everything is ending.

There are some lines from a Russian revolutionary writer, Vasily Rozanov, that capture the feeling here: “The show is over. The audience get up to leave their seats. Time to collect their coats and go home. They turn around. No more coats and no more home.”5

Richard, you talked about intellectual versus professional motivation. Or did you use a different word?

RA: I think I said goals.

NB: We have intellectual goals and professional goals backlit by collapse and austerity. How should young people sort this out? It feels genuinely difficult to know what to do. For me, it’s important to highlight the fact there are legitimate ways to be a philosopher outside the academy, and not presuppose when giving advice that it’s pro philosophy or bust.

CL: What do you have in mind?

NB: Here’s something small I’ve tried out. When I teach graduate students, I like to assign at the first meeting a chapter from a biography of Emerson. The chapter is from Robert Richardson’s outstanding book Emerson: The Mind on Fire and it describes Emerson’s work as a lecturer.6 After Emerson quit being a Unitarian minister, he traveled around delivering talks, which we now know as his essays. He’d sometimes travel to frontier towns, in Ohio and Michigan, and out of the way places where there weren’t many established schools. Folks on the frontier couldn’t usually go beyond grammar school, but they still wanted to learn. For his lecturing, Emerson prepares all of these beautiful, electric talks. My suggestion to grad students is that Emerson shows us philosophy beyond the bricks and mortar of institutionalized, academic philosophy. Without an academic appointment, he contributed to intellectual life. I want my students to consider him as a representative of a different way—and to open their minds to other ways. Because the fact is, as I say at the seminar’s first meeting: Most of you will never get tenure-track or tenured teaching jobs. So, what do you do when you go to grad school in philosophy today? How do you act when you know the system is melting down and you have to escape?

CL: The question is something like, Why keep abiding by these norms? Why jump through the hoops, when jumping through hoops is unlikely to do anything for you professionally or spiritually?

NB: Yes, I believe some young philosophers feel the force of that question, even when their teachers don’t.

CL: Why work on these small, niche projects when the discipline is collapsing and you don’t get any sort of personal benefit from doing this?

NB: Yes. Maybe you earn your Ph.D. and stop doing philosophy, feeling glad that you took a bunch of grad seminars, comp exams, and published in Philosophical Studies or Synthese or The Transactions of the Peirce Society. It’s different strokes for different folks, of course, but then I remember that the academic system is merciless. Even if grad school goes alright for you, I hope you can put your own goals ahead of the system’s goals—which are mainly to use you as inexpensive labour and spit out your bones.

RA: I certainly agree with you that for a lot of students, an academic career isn’t going to pan out. There is a real risk that they will be exploited as adjuncts when they could be transitioning into better careers. That said, in my experience, most people find their way into other careers. I think just about people Charlie and I knew in grad school, some of whom are now VPs in tech companies or at banks, others have started their own businesses, and some of us managed to find work in the academy. No matter what area you go into, you have to keep learning. Otherwise, other people are going to do better than you in whatever career you choose. That might be the most valuable thing to gain through getting a Ph.D.—getting better at teaching yourself new material and staying on top of current research.

NB: I like your emphasis on learning how to learn. On that topic, what’s the most frustrating situation you’ve had to deal with while doing research?

CL: Not finding the tools I need to communicate my ideas. Sometimes, the ideas are inchoate and ill-formed, and I’ll need some concept that’ll help me convey what I have in mind, but I’ll have a hard time expressing the idea in a way that connects with the current literature. For instance, I wrote something on “trappings of expertise,” and reviewers would ask, ‘What the hell is that?’ A better framing uses “signs” or “signals” of expertise, but I didn’t find that until later. Work on signs and signals and signal systems could have helped me communicate more efficiently.

NB: I’m unsurprised you find yourself hunting for the right language to frame and conceptualize your projects. Does part of the challenge stem from the distinctive intellectual project you’ve been pursuing since grad school? You approach empirically-infused questions about philosophy of mind, language, and social epistemology from an Aristotelian perspective, but your interlocutors typically approach things quite differently. Is that part of the story?

CL: Your description is about right. I’m interested in empirically-infused philosophical questions about mind, language, and social epistemology, and my approach finds some inspiration in Aristotle and Wittgenstein.

NB: Oh, I had forgotten your interest in Wittgenstein.

CL: I invoke the authority of Saint Elizabeth Anscombe for the coherence of this pairing. I don’t think many others in the areas I like to think about bring Aristotelian and Wittgensteinian baggage to the table.

NB: Can you give an example of a project that weaves together these influences?

CL: Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics sets up his Politics. Aristotle wants to figure out what’s good for us in order to figure out what kinds of societies can promote what’s good. To me, this suggests that epistemic or intellectual character is important in the marketplace of ideas—broadly, the circumstances where we inquire, learn from each other, and arrive at our beliefs. A further idea I find in both Aristotle and Wittgenstein is that epistemic agents’ history matters for epistemological theorizing. I mean, how someone got to be the way they are intellectually is important for thinking about their knowledge or lack thereof.

NB: So you’re trying to theorize about people’s knowledge by placing them within a rich historical and social context?

CL: Yes, that’s the idea. Here’s one way I have tried to understand the richer context that can help explain epistemological phenomena. I’ve used computer simulations to model epistemic agents. Think The Sims, but you get to define all the rules. In one article, I conceptualized belief transmission as analogous to a contagion. Beliefs spread in a community by contact. As long as there’s some possibility for agents to update their beliefs about an issue—as long as they are susceptible to influence from others—the entire population will converge on a single belief. But what struck me as interesting is how often people don’t converge. Is a hotdog a sandwich? Is pineapple on pizza acceptable? So, I considered a possibility that might explain diverging beliefs. Dogmatists are agents whose beliefs don’t change. On my view, dogmatists have neither good nor bad epistemic characters, but they have a high degree of steadfastness. It only takes a few people, a few true believers committed to positions X, Y, and Z, to keep those beliefs spreading, kind of like an Epistemic Typhoid Mary.

NB: What are the implications of your model?

CL: Here are two. First, instances of polarization—or even of consensus—can come about because a handful of people with different beliefs simply won’t budge. A lot of cases of political polarization are like that, I think. And, second, the converted end up making more disciples than the true believers. After a while, the number of converts surpasses the number of dogmatists. Dogmatists are eventually surrounded by converts—they’re preaching to the choir. But converts are on the outer edge of the spread of some belief, and since they tend to talk with agents holding different beliefs, they’re in a position to change others’ beliefs.

NB: Richard, what problems have you dealt with as a researcher?

RA: Since a lot of my work focuses on Peirce’s thought and many important manuscripts have not been published, the most frustrating part of my research, especially early in my career, was getting access to his manuscripts. Part of the issue was financial—it cost a lot to travel to the archives. If I needed to return to double-check quotations or to re-read passages, that was cost prohibitive.

NB: You couldn’t take photographs in the archives?

RA: Now you can, but I guess that years ago it didn’t even occur to me. But that wasn’t the only problem.

NB: What else was going on?

RA: Between my heavy teaching load and my family at home,7 I didn’t have much time to travel. And a third part of the problem was figuring out the complicated system of references, what had been published and where, what hadn’t been published and how to access it. You have to have a more senior Peirce scholar teach that to you. For me, moving to Boston was hugely beneficial because I could take public transit to the Peirce archives and Houghton Library. Also, PDFs of many unpublished manuscripts have since been posted online.

NB: As you were trying to find your way in academic philosophy, what was your greatest disappointment and how did you deal with it?

RA: There wasn’t a single disappointment. It was more the repetitive stress of being on the job market.

NB: How many years were you searching before you moved to Boston College?

RA: Too many, because I went on the market before I finished my dissertation. I guess it was at least six years. You know, you brought up the collapse of the USSR earlier and I was thinking: 2008 was the housing crisis and recession. At that time, I was completing the Ph.D. and my daughter had just been born. It took a long time for the market to recover, even in academic philosophy, and even then it didn’t fully recover. Now we’re facing declining enrollments at colleges across the US. And the stresses associated with that uncertainty and just wondering, “Well, what the hell am I going to do with myself if this doesn’t work out?” I guess it’s not right to describe that feeling as a disappointment. I guess the disappointment was sending out dozens of applications and hearing nothing.

NB: How did you deal with that?

RA: Looking back, I probably had periods where I was depressed. Maybe I dealt with a low mood by exercising and burying myself deeper in books. My wife, Božanka, will probably tell you that I was not a pleasant person. But also because of her support—including the fact that she had a good job—I wasn’t panicked. Having some financial stability made it possible for me not to despair as much as I probably would have otherwise.

NB: What about you, Charlie?

CL: As far as disappointment goes, I experienced similar things. Sending out hundreds of applications is demoralizing. When I was looking for a job, my wife was working as a campus minister at a Catholic high school, which I don’t know if you guys know this, but: Catholic schools don’t pay employees a whole lot. I was adjuncting and trying to make ends meet. For me, there was little room for error. When I was hired at Gonzaga, it was on a one-year contract, renewable up to three times. During the first year, a tenure-track position opened up in areas I was well-suited for. I didn’t have any room to be less than the best candidate for that job. I took everybody out for coffee or lunch. During my first year here, I was a gregarious son of a bitch.

NB: Are you still a gregarious colleague?

CL: My office is currently at the end of a hallway that leads to a parking lot—not a lot of reasons to walk my way. I like my solitude.

- RA: It was a terrible decision that luckily turned out okay. I would advise anyone against doing a Ph.D. without funding.

CL: I couldn’t agree more. It’s a minor miracle we got through it. I don’t know if you feel similarly about yourself, Richard, but I think that having to grind so hard for years made me a better philosopher, better teacher, and definitely a more competitive job candidate. How many other candidates were applying for assistant professor positions with experience teaching 40 to 60 classes?

NB: When did you come to the view that the grind was a benefit to you, not merely a crushing burden?

CL: I guess I’ve come to see things this way only quite recently—definitely after I got a stable job and after tenure. To be perfectly honest, I was angry at and resentful of so many people during grad school. My situation didn’t seem fair. Even so, the grind forced rapid development of skills that were invaluable on the tenure-track.

NB: How did the grind benefit you, Richard?

RA: I definitely agree with Charlie that it made me a better teacher and a better philosopher. I’m not sure that it made me more competitive on the job market, though. I think having taught introductory courses 10 or 15 times would have been just as good from a hiring committee’s viewpoint. With that said, Charlie was able to teach a wider range of classes than I was, and I suspect that did make him more competitive. Perhaps my advantage was teaching at a more prestigious institution—NYU. Anyway, I’m sure that teaching NYU’s Social Foundations course prepared me well to teach the core course, Perspectives, here at BC.

NB: I think you’re correct: teaching a variety of courses can boost a candidate’s profile. Covering Intro to Philosophy over and over again means diminishing marginal returns for a job seeker. But there’s a further issue here about marketability, I think. Sometimes search committee members look at candidates with lots of teaching experience as somehow less desirable than ones with only a little. The old-timers look “shopworn.”

CL: Your point about looking shopworn is interesting and odd. That reads to me as: We don’t want someone with too much experience!

RA: I always leave the grocery store empty-handed because if the food tasted good, someone would have already bought it. ↑

- CL: Before Richard and I started the existential graphs reading group, we had a reading group on George Boole’s The Laws of Thought. It was a lot of fun. A few other grad students joined us because they thought the book would help them on the department’s Logic Exam. Spoiler alert: it did not.

NB: Did anyone flunk the Logic Exam because they got too deep into Boole?

RA: No, but I failed it the first time because I tried to use Peirce’s existential graphs. The professor grading the exam wouldn’t allow that.

NB: That’s genuinely hilarious. Now I need to know: What are existential graphs?

RA: At the sentential level, existential graphs, or what Peirce called the alpha graphs, represent logical structure through a sheet of assertions and cuts. A sheet is basically a sheet of paper or a blackboard. Cuts are non-intersecting closed curves—usually circles or ellipses. A sentence written on the sheet is (asserted to be) true. Two sentences on the sheet are both (asserted to be) true. Accordingly, juxtaposition on the sheet functions as the wedge (or conjunction connective). Cuts negate whatever they enclose. Sentences can be abbreviated with letters. If we join the endpoints of complementary parentheses to create ellipses, then:

ab = a&b

a(b) = a&~b

(ab) = ~[a&b]

(a(b)) = a->b

((a)(b)) = avb

Since sheets are spread over two dimensions and mere juxtaposition functions as the wedge,

b

a = ab = ba

(That might read a little strange. It is: a ‘b’ above an ‘a’ is the same as an ‘a’ to the left of a ‘b’, which is the same as a ‘b’ to the left of an ‘a’.)

For this reason, rules such as commutation and association are otiose. Other rules are given for transforming graphs, such as double cut insertion, by whichab

can be transformed into:

a((b))

or:

((ab))

or:

((((a))b))

And so on. By double cut erasure, these transformations could be reversed. Double cut insertion and erasure, then, are functionally equivalent to double negation introduction and elimination. Of course, other rules are needed for a syntactically complete system, and Peirce provides them.

The beta graphs, which are roughly equivalent to quantified first-order predicate logic, build on the alpha graphs, much as first-order logic builds on sentential logic. I say “roughly” because there are some interesting differences, such as the way in which the beta graphs and first-order logic handle proper names. Peirce also introduced a dashed curve or broken cut to represent the modal operator ‘possibly not’ and proposed a system of gamma graphs to handle modality.

The best introduction to Peirce’s existential graphs remains Don D. Robert’s The Existential Graphs of C.S. Peirce (De Gruyter, 1973). Currently, Ahti-Veikko Pietarinen is editing a three-volume (in five books) collection of Peirce’s writings on the graphs titled Logic of the Future (De Gruyter, 2020–).

NB: Logic of the Future—a bold title!

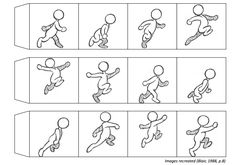

CL: I recall reading in Robert’s book that Peirce also said that, if one were to put every transformation of a graph onto its own page and then treat it like a flipbook, then one would see reason in action. Am I misremembering?

NB: Like this?

RA: It is very much like that, Nathan. And yes, Charlie, you’re remembering correctly. Peirce called them the “moving pictures of thought” and he was partly inspired by the work of Eadweard Muybridge and Marey into “chronophotography.” Frithjof Dau illustrates a simple proof with a video here. And I once wrote an article about this.

NB: Let me ask a potentially dumb question. Are existential graphs supposed to be a replacement for more standard approaches of logical notation, or just a complementary addition to them?

RA: That’s exactly the right sort of question to ask: Why add another system of notation to the one we already have, especially a system that can’t be easily typeset? Although we could replace our base 10 system of numeration with a base 2 system, why do so when people already competently use the former? And about the typeset: for the few articles on the graphs published during Peirce’s lifetime, a Japanese artist made printing blocks for the images.

Anyhow, I doubt very much that the existential graphs are the “logic of the future,” but I would note that just because they are not the logic of the future, it doesn’t follow that studying them is not worthwhile.

NB: Say more.

RA: Here are four reasons for studying the existential graphs, even supposing they are not the “logic of the future.” First, studying other languages can improve our understanding of our native language. I think that’s true of logical languages, too. Second, places where one notation diverges from another—for instance, on how existential graphs vs. first-order logic handle proper names—can shed light on presuppositions implicit in a language. Third, a graphical system of logic might be more apt for some uses than others, as a graphical representation of the NYC Subway might be more useful for navigation than an alphabetical list of all the stations and their connections. Finally, it’s surprisingly easy to experiment with the existential graphs, since most of the rules are based on complementary operations in evenly vs. oddly enclosed areas—that is, the number of cuts enclosing a sentence letter, at least in the alpha graphs. I call this “notational fecundity.” That’s the ease with which one can develop notational extensions and experiment with them.

NB: What did Peirce’s graphs actually look like?

RA: Here’s a manuscript page featuring the beta graphs:

The heavy lines function as the existential quantifier and the letters are now predicates, so the first graph is “something is W”, then “nothing is W”, “something is not W”, “everything is W”, “something is W and V”, and so on. ↑

-

NB: Do you still follow the Atkins’ Diet?

RA: I do. But this semester I’m taking an intro to music theory class, so most of my reading has been about music theory. It has interesting connections, I think, to the “philosophy of notation”—a phrase Peirce coined but an area that has received little attention. ↑

- The lost book project was recently reconstructed from fragments in Dewey’s personal papers. ↑

- I have followed a paraphrase of Rozanov’s words from the artist Christopher Wool’s “UNTITLED (THE SHOW IS OVER…),” a 1990 word painting that features this text. For Rozanov’s original text in English translation, see The Apocalypse of Our Time and other writings by Vasily Rozanov, edited with an Introduction by Robert Payne (Praeger Publishers, 1977), p. 277. ↑

- “The Lecturer” in Robert Richardson’s Emerson: The Mind on Fire (University of California Press, 1995). ↑

-

NB: You were both in relationships when you went through grad school. Have you thought about what might have happened if you had been single? Would you have made it?

CL: I’ve wondered about this before. There are trade-offs, of course. Being single, I would have had more time to read and write and I wouldn’t have had the kinds of concerns that come with being married—visiting in-laws, balancing work time and home time, negotiating married life, and so on. But if I were single, I wouldn’t have had Michele’s incredible support. Whenever I was overwhelmed or depressed, she was there. Would I have made it without her? Probably. But it’s hard to estimate how severe the damage to my well-being would have been. I’m confident that the damage would have been significant.

RA: In my case, if I had been single, I would have made it through graduate school, but I don’t think I would have established a career in academia. It’s quite hard for me to imagine what would have happened, though I’ll bet the alternative involves alcoholism, depression, and a lot more exploitation through being an adjunct lecturer.

CL: Same here. Jack Torrance but without the murder.

NB: Of course, Jack Torrance was a writer. Did he have any helpful writing advice?

CL: Jack’s philosophy of writing is “all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.” ↑